Small to Big by Comparing State-by-State

How do we turn a narrow topic on a local story into a year-long project? Take that narrow topic on a state-by-state tour and compare how laws and data and history and stories differ in 50 comparable ways. This page is a set of real-world examples of how to find focus in a larger issue, and make a big project by looking at the U.S. state-by-state picture.

The Guardian's Circle of Same-Sex Rights

Same-sex marriage is now status quo in America, so it's harder to appreciate the information value and depth of the Guardian's 2012 visualization of gay rights in the United States:

In his "how-we-made-this"-post, the Guardian's Feilding Cage writes that his immediate instinct was to not do a map, because virtually every other news site was doing a map.

As an example, here's a perfectly serviceable map from Mother Jones in 2012:

But the inherent weakness of a map is that we can typically fit only a single data layer before things get confusing. So a map that intends to say something about gay rights can only clearly converse about marriage.

As Cage puts it:

I didn't want to focus solely on gay marriage. The political dialogue seems to define the quality of life for gays and lesbians based on their right to marry, but it's much more complicated than that.

This is not so much a commentary on visualization, but on the act of research, counting, and thinking about what you count and don't count. Virtually everyone who made a chart about same-sex marriage also had an opinion about the bigger picture of same-sex rights. The choice to track only gay marriages state-by-state is an efficient decision, but it wasn't the only way to think about the issues.

So why don't we think about things in more detail. Because it takes a lot more thought and time. Cage writes:

Gathering data for a project like this is a challenge because of how much variation exists between states and whether the precedent originated as a definition in the constitution, as an amendment to it, or was determined by the courts. Using employment as an example, state definitions vary to include some combination of public and/or private sector jobs and whether sexual orientation and/or gender identity was included. To complicate matters further, local laws and federal regulations also extend additional or partial rights.

It's easy to look at the final product and think that everything is as neat and clean as the Guardian's design:

But as the fine print reads under the Employment subheading, the chart doesn't differentiate between states that protect against discrimination in public jobs vs private jobs, hence why North Carolina and many other states is a gray slab, even though it prohibits discrimination based on sexual orientation and gender identity in public jobs (nevermind Florida, in which protection of public employees is county-by-county).

The Guardian's extra work and thought towards data results in a visualization that tells a far more important and nuanced story than gay marriage. The Guardian's chart isn't as straighforward as a map, but it has more fidelity with reality, and to all the parts of life that are important but aren't marriage. With gay marriage now legal, the state-by-state differences in the other aspects of life is even more critical to track:

Via The Tennessean: Gay marriage decision opens legal issues in Tennessee, Sept. 2 2015:

The court’s ruling granted same-sex couples the Constitutional right to marry — along with the benefits of marriage. But same-sex couples will not necessarily receive all of the benefits because Tennessee’s laws assume that marriage is between a man and a woman. The collision between this assumption and the fundamental right of marriage will inevitably create significant legal questions.

The rest of this very long article is just a bunch of examples about a general concept: Understand something at a small scale. Then compare. In this lesson, we look at stories that come from comparing across U.S. states, because the differences are meaningful, and it's worth getting used to the concept of bureaucracy and geopolitics, even if it's just the U.S.

Go small, then big

If you're an idealistic journalist, of course you want to report on an issue as important as war, justice, health care, equality. And you wan to report on that issue nationwide, if not worldwide.

But thinking of things as boldly and broadly as, "I want to report on criminal justice!", likely means you have nothing interesting to say about the topic, as if "criminal justice" were one topic with a single debate and solution.

It's better to focus on the smaller issues and build the big picture from there. The section of Public Service Pulitzers weren't given on the basis of how reporters exposed "evil" and "inequity", but "comprehensive coverage of sexual abuse by priests, an effort that pierced secrecy" and exhaustively researched series exposing deadly medical problems and racial injustice at a major public hospital"

What are the smaller issues of criminal justice? As a start, policing, courts, and prisons. And each of these have their own sub-topics: under courts, we have funding public defenders, prosecutorial misconduct, and judicial appointments. Policing includes use-of-force incidents, COMPSTAT, hiring policies. And prisons includes public vs. private, overcrowding, solitary confinement, prisoner safety, etc.

The Difficulties in Going Small

To illustrate how you can get to the big issues by focusing small, let's go to an extreme: Shane Bauer's epic first-person write-up for Mother Jones of his four months as a private prison guard.

This is a "small" story because it is built off the first-person experiences of Bauer. But with any investigation of seriousness and significance, there's more to its reporting than excerpting a 4-month diary. The dates of Bauer's story – December 2014 was when he joined the prison, and July 2016 is when the Mother Jones piece was published – is one clue to the extra work.

In the editor note by Clara Jeffery, editor-in-chief of Mother Jones: He spent four months as a guard at a CCA-run Louisiana prison, and then we spent 14 more months reporting and fact-checking.

Mojo's and Bauer's work is something to aspire to. But for the purposes of this class, we don't have the physical time to devote 4 months going undercover, or a full-year doing additional reporting. So we set our scope a little bit broader, capturing information that we can find via the Internet, books, and telephoning around.

For what its worth, the sidebar that accompanies Bauer's main writeup, The Corrections Corporation of America, by the Numbers, is the perfect example of the kind of data sidebar that is acceptable as a final project for this class. The research can be done via the comfort of the browser, and done before or after the main reporting. It is short, but adds worthwhile context to the personal experience of working at a private prison:

Reporting on prison overcrowding

OK, let's take on a less ambitious topic: prison overcrowding. It's no less important, and is obviously related to the phenomenon of private prisons, but overcrowding is something that is related to prison budgets. And, there's likely to be actual prison population counts in the public record.

What makes this "easier" is that just about anyone can get public records, without worrying about time or travel limitations.

Local angle

A doable story for the novice reporter is to look at overcrowding at just a single prison. You don't have to tell the reader what prisons are like statewide or nationwide, just what's going on in one prison.

Here's an NPR story that focuses on the Folsom State Prison, made famous by Johnny Cash, and uses it as a microcosm of the state of California's prison crisis:

Folsom Embodies California's Prison Blues

Folsom was built to hold 1,800 inmates. It now houses 4,427. It's once-vaunted education and work programs have been cut to just a few classes, with waiting lists more than 1,000 inmates long.

Statewide angle

Now let's take a broader view. What is the state of prison overcrowding for the state of California? Here's a Reuters' story, several years after the NPR story, that focuses on how recent reforms have reduced inmate numbers but not costs:

California prison reforms have reduced inmate numbers, not costs:

In 2012, under court order to reduce prison overcrowding, California announced an ambitious criminal justice reform plan that promised not only to meet the court mandate but also to improve criminal sentencing and “save billions of dollars.”

Now, three years after implementing the changes, California has reduced its prison population by some 30,000 inmates, and the state is in the vanguard of a prison reform movement spreading across the country, with support from both the right and the left. But the promise of savings – a chief goal of prison reform nationwide – has not been realized. Instead, costs have risen.

The angle here is: prison populations seems to have fallen, but yet costs have risen? It's a story that goes beyond just overcrowding, and it also feeds into a bigger picture of how the prison system is funded, and the incentives for building private prisons.

Same topic, but go nationwide by going state-by-state

The Folsom State-focus, and the California statewide focus are all solid stories. But thinking towards a project that befits a master's level thesis, we don't have to expand our topic of prison overcrowding. Instead, we could look at things, state-by-state:

For example, here's a USA TODAY story that goes nationwide, but looks at an even narrower topic of overcrowding: the aging prison population.

Aging prisoners' costs put systems nationwide in a bind

The fiscal, legal, social and political challenges of housing this country's graying inmates have arrived with full force at precisely the time when states, and the federal government, are looking to rein in spending. A problem swelling for decades has become "a national epidemic," according to a 2012 report by the American Civil Liberties Union.

Summary: It's not just that prisons have too many inmates, but they have too many old inmates, and these inmates are more expensive to take care of, which means less money to take care of all the inmates in general.

Digging deeper, we see that the USA Today story is heavily based off of a 2012 ACLU report, The Mass Incarceration of the Elderly. Let's see how the ACLU does things:

From 1980 to 2010, the United States prison population grew over 11 times faster than the general population. During this time, the general population increased by 36%, while the state and federal prison population increased by over 400%. The number of elderly people in our prisons is growing even faster.

The fact that prison populations nationwide have quickly grown is not new, particularly to an organization such as the ACLU. So they've taken a different angle: that we need to worry about the age demographic of each state's population.

Here's a chart showing the big picture, that the elderly prisoner population is growing at an unprecedented rate:

And here's a chart that shows the power of a more granular view: change of older prisoners vs. all prisoners by state. And in particular, southern states:

And here's a chart that focuses on one state, Michigan. They could repeat this chart for all 50 states, of course:

The point is that even taking a narrow slice of a topic – elderly U.S. prisoners – and starting at a local level – a single prison or state prison system – we can quickly build out a indepth project by just looking at that same narrow slice of a topic for all 50 U.S. states.

This works because:

- The U.S. Constitution generally allows states to have widely varying laws and statutes.

- 50 different entities is not a non-trivial number of things to look up.

After conducting this widescale research, we have a compelling story that provides new insights to the broader topic of prison reform. And we can do it in a much more efficient, feasible way than someone who starts off with, "I want to tell an important story about prison reform!"

Justice for sexual assault victims

Let's look at another subtopic in justice: how sexual assaults are investigated and prosecuted.

The sensitive nature of these crimes make them inherently difficult to properly report, for the same reasons that they are inherently difficult to prosecute: victims are reluctant to come forward, nevermind publicize their cases. This makes starting at a personal level one of either chance (you personally know a victim or advocate), or, you've done enough reporting and researching to gain the trust of victims and their advocates.

Let's assume you are in neither situation. How can you report significantly about sexual assaults and the justice system?

Local Angle: the Brock Turner case

This case is relatively recent and its ramifications are still taking effect just months after Turner's conviction and imprisonment. But to review:

- In March 2016, Brock Turner was found guilty on 3 felony counts.

- In June 2016, Turner was sentenced to 6 months in county jail

- Around a day later, the victim's letter was published in BuzzFeed. The letter was already released as part of the court record, but BuzzFeed received the letter from a friend of the victim. And BuzzFeed's reporter, Katie Baker, was trusted by the victim's friends.

- Stanford law professor Michelle Dauber, a personal friend of the victim, continued to highlight and tweet parts of the court record, which were also reported on by the media.

- In September 2016, Turner completed his jail sentence and went to Ohio to register as a sex offender.

- By the end of September 2016, California Gov. Jerry Brown signed Assembly Bill 2888, which "will prohibit a judge from handing a convicted offender probation in certain sex crimes such as rape, sodomy and forced oral copulation when the victim is unconscious or prevented from resisting by any intoxicating, anesthetic or controlled substance"

- Gov. Brown also signed Assembly Bill 701, which "will expand the legal definition of rape so it includes all forms of nonconsensual sexual assault when a judge is deciding the sentence of a defendant and connecting victims with services."

On a sidenote, the power of showing documents; Professor Michele Dauber's highlighting of the court record helped to raise anger and attention towards Turner and his light sentence. Her tweet is just a tweet, but is much more visceral and direct than linking to the entirety of the court record:

A competing controversy is the argument that society unfairly metes a lifetime amount punishment and stigma to sex offenders. The law that forcesTurner to register as a sex offender for his entire life, imposes that penalty on lesser offenders whose cases don't make the news.

More local angle: How the California laws got written

Worth noting that were it not for the impact of Turner's victim statement, these laws may not have been created. According to the LAT's interview with Assemblywoman Cristina Garcia (D-Bell Gardens):

Garcia said she was moved to file the bill when reading the impact statement written by the victim in the Turner case. The victim was not allowed to call the crimes committed against her “rape” under California’s laws. “I wanted to make sure that one piece was righted,” Garcia said. “There is a lot of work we still have to do to end rape culture in our country. But calling rape what it is, is a great first step.”

State-by-state: Why not mandatory sentencing everywhere?

If this is such a commonsense law, why did it take a horrific crime and spectacle of a trial to make it happen? As it turns out, mandatory sentencing law does not sit well with all groups. So as the California laws go into effect, a forward-thinking indepth piece would look at how this issue has come up in other states. Which states have passed similar laws under similar circumstances? And, are there any states that have rolled-back these laws?

Again, strategy of doing research state-by-state can bring important clarity and insight even when we don't yet have the personal trust of victims and victim advocates.

Searching for older newspaper stories via Google-fu and LexisNexis

Finding these stories pre-Brock-Turner takes a bit of work. Because a Google search for "state mandatory prison sentence sexual assault" will be innudated with stories about Brock Turner.

If you want to use Google, you will want to use the minus-sign operator to exclude all results with "Brock" and/or "Turner":

state mandatory prison sentence sexual assault -brock -turner

e.g.

https://www.google.com/search?q=state+mandatory+prison+sentence+sexual+assault+-brock+-turner

Not a lot of news stories. A cursory search reveals a 2014 Al-Jazeera America story, Florida becomes the harshest state for sex offenders, which ostensibly has done some research of the state-by-state picture. However, its assertion that Florida is the "harshest state" is based on the fact that it "it's legal to lock someone up indefinitely for a crime they haven't yet committed", which is a whole different ballpark.

LexisNexis for searching by date

Let's try LexisNexis Academic search which will only work if you're on campus. With LexisNexis, not only do we have the flexibility to exclude terms such as "Brock" and "Turner"…we can facet the search by publishing date. Limiting the search to between 2010 and 2015 effectively excludes all Brock Turner stories because, before his conviction, no one cared about Brock Turner, at least at the national news level.

A query for "mandatory minimum prison and states and sexual assault" between 1/1/2010 and 1/1/2015 turns up numerous stories, though it'll take more work to find nationwide projects:

However, a few state-level stories are evident:

A May 10, 2010, story in the Telegram & Gazette (Massachusetts), titled, "Plea bargaining; In child rape cases, prosecutors weigh risk of acquittal, further trauma to victim", the reporter looks at 3 cases after a 2008 state law, modeled after Jessica's Law, was enacted to establish mandatory minimum sentences for child sexual assault. In each case, the defendant was allowed to plead guilty to a reduced charge of statutory rape which did not have a mandatory decade-long prison sentence:

…the parents of the victims did not want their children to have to testify at trial, and in the Sheehan case, "we had real concerns with the witness getting through the case and tolerating the trial process," the district attorney said. Mr. Early also noted sex offender counseling and GPS monitoring were ordered as conditions of probation in each case. "We are going to be taking cases under these charges to trial, but you just don't do it without considering things such as what are the chances of winning the case, what are the weaknesses of the case, what is the best balance to keep the community safe," the district attorney said. When plea agreements are made, the mandatory minimum sentences provided for under the new law can be used by prosecutors as a "bargaining chip," according to Mr. Early.

via the Salt Lake Tribune, Utah locking up more sex offenders, December 30, 2011, there's a remark that removing mandatory sentences increased the number of sex-offenders who are in prison:

Utah has 10 times more sex offenders locked up than it did 30 years ago. Since 1980, the rate of felony sex offenders has risen steadily, now making up nearly one-third of the prison population… While prison sentences increase in length, the sheer number of offenders being sentenced for sex crimes is on the rise as well. The number of offenders sentenced more than doubled in the past 30 years, and the number of convicted felons sent to prison jumps after 1996, when the state eliminated its mandatory-minimum prison sentences. Policymakers thought mandatory minimums would result in more sex offenders going to prison, but in reality, fewer were sent away because it encouraged lawyers to seek plea deals for lesser charges, Skinner said. "When offenders' only option is to plead to something that has a mandatory minimum, they were less likely to volunteer for that," she said. "Because those kinds of cases are so difficult to try, and the victims are very fragile, prosecutors were more willing to give plea agreements to lesser offenses that didn't have that mandatory sentence with it."

Doing a different query on LexisNexis, limited to stories about Utah, sex offenders, and mandatory sentencing, from 1/1/1994 to 1/1/2008, finds another Salt Lake Tribune story, this one in which lawmakers are accused of being weak on punishing child molesters:

(note: After finding the story on LexisNexis, I found it on Google by looking for the exact headline. I don't think I could've found these old stories otherwise)

Officials defend current penalties for sex offenders, June 9, 2006:

"We've been inundated with calls that Utah is weak on crime," Utah Sentencing Commission director Thomas Patterson said Wednesday. But Patterson and other members of the commission insist the opposite is true…

Utah tried minimum mandatory terms for child sex crimes from 1983 to 1996, before repealing the law and returning sentencing discretion to judges and the state's five-member parole board.

"When we got rid [of minimum mandatory terms], we learned our system works a heck of a lot better without it," said Paul Boyden, executive director of Utah's Statewide Association of Prosecutors.

To sum up, Utah had a huge increase in imprisoned sex offenders without mandatory minimums, because, without mandatory minimums, the accused had an incentive to take a plea bargain. With minimum sentencing, the accused would take their chances with the system, and often victims weren't willing to testify. Unintended consequences, etc.

Local angle: Bill Cosby and the statute of Limitations

Coincidentally, the same week that the laws related to Brock Turner were signed, Gov. Brown also signed Senate Bill 813, which eliminates the statute of limitations for sexual assault victims to bring an accusation to court. Previously, such crimes in the absence of DNA evidence must be prosecuted within 10 years of the offense.

This Senate bill was sparked by testimony of alleged victims of Bill Cosby that could not go to court because they had missed the 10-year-deadline to file charges.

“War criminals, no matter how many decades have passed, cannot evade prosecution,” Bernard told the Senate committee. “I am asking you to do the same thing for us, rape survivors, who survived the war upon our body.”

Nationwide angle: State-by-state statute of limitations on rape

Again, the question is worth asking: Why haven't statute of limitations been eliminated already? And, where is California among the other states in taking this step?

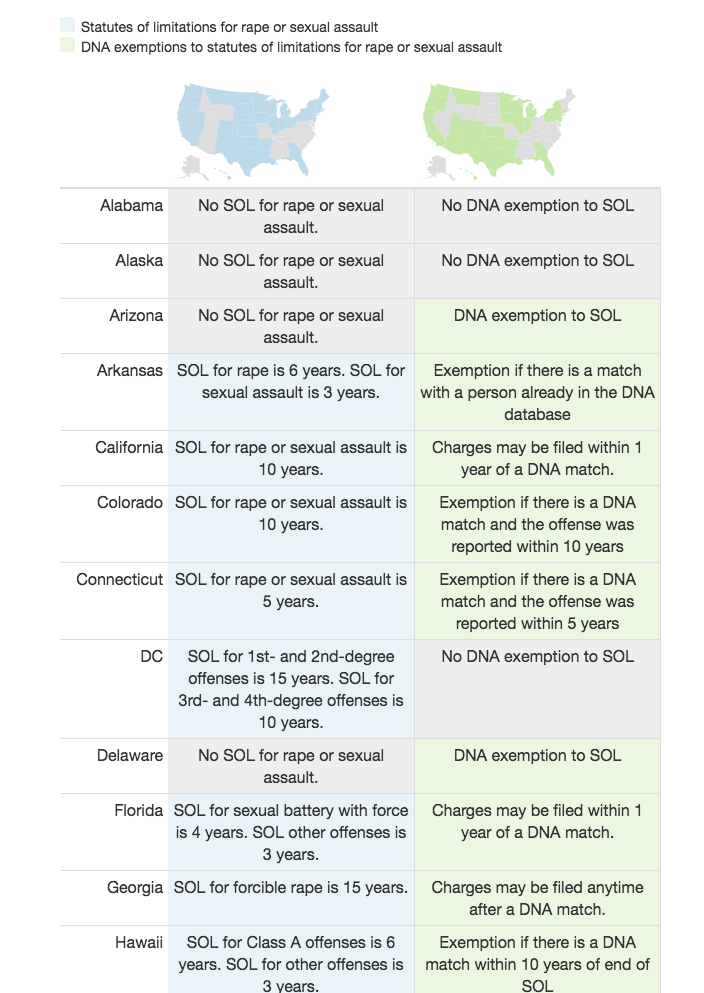

As it turns out, finding the state-by-state picture of statute-of-limitations is much easier than finding it for mandatory sentencing or definition of sexual assault. Mother Jones published a comprehensive data table/map in late 2014, though it obviously isn't updated for California:

The above table is basically a spreadsheet with a convenient map visualization that let's us see things at a nationwide glance. There is nothing stopping you, a student of this class, from producing something something just as useful and insightful, knowing what little you do know of spreadsheets.

You could even extend on this work for a thesis project, by researching how and why the current policies were put in place. For California, for example, you would note that the Bill Cosby case effected new (and quickly approved) legislation that eliminates statute of limitations. What about the 16 other states that also eliminate such limitations.

Looking at the map provided by Mother Jones, isn't it interesting that a good number of southern, conservative states eliminate SOL. And the states that have SOL of fewer than 10 years, such as Arkansas, Connecticut, and Oregon – why is that?

Abortion

One more example of how to find a feasible angle to a highly personal and heavily-discussed topic: abortion.

Both sides of Roe vs Wade see it as settled law, barring a massive change in the Supreme Court. Yet pro-life/pro-choice advocates are still active at the legislative level because things are not as simple as "Does a woman have the right to an abortion?"

The pro-life side, for example, has effected meaningful rollback to abortion rights by thinking in terms of women's health. The Partial Birth Abortion Ban Act was signed by President Bush in 2003, found unconstitutional in district court, before being appealed up to SCOTUS, which upheld the federal ban.

The NYT reported in 2007 that the decision was seen as vindication of the pro-life strategy to focus public sentiment on the fetus rather than womens rights.

In Planned Parrenthood v, Casey, the Supreme Court ended up reaffirming the woman's right to abortion, but allowed that states could enforce precautions and caveats, including the requirement of parental consent for minors seeking an abortion.

The big picture here is, if the fight over abortion involves these specific ways at looking at women's health, fetus viability, etc., which are further diversified by how states can legislate, then a project that does important reporting on abortion virtually necessitates a state-by-state look.

In the next two sections, I'll cover the parental notification laws of abortion, and compare the approach of a local, typical daily story, to a project of nationwide scope, and how both are doable by you for the scope of this class and for a master's thesis.

Local angle: Parental notification in Colorado

I had to pull this Denver Post story from the Lexis Nexis archive:

Few bypass abortion rule - via the Denver Post, August 15, 2004.

Judges can override parental-notification law, but not many teens try Groups backing the rule fear that the requests are being rubber-stamped, but jurists dispute that.

As far as I can remember, this was the very first data story that I had ever done, even though I didn't know it at the time. The background: Colorado had in the past 9 months passed a law compelling doctors to notify a minor's parents before performing an abortion. For this law to have bipartisan support, it included an exemption called the judicial bypass: a minor in extreme circumstances could go to a judge and ask for an exemption.

Planned Parenthood's short writeup is helpful, as it contains a list of laws by state: Parental Consent and Notification Laws

I didn't know anything about this specific part of abortion law, or Colorado's recent legislative activity. So getting an update on whether the exemption was being used was my editor's idea. Or else, that's what I narrowed it down to. It seems obvious that the story should be about how many Colorado minors had abortions a year ago before this parental notification law was signed, and how many have been recorded afterwards.

How to find data when no official data is kept

However, it's safe to say I had no idea how to get even those numbers. So looking at number of judicial bypasses probably seemed like a logical facet, because there might be a centralized count of those somewhere.

As it turns out, the most centralized data I could find was at the county courthouse level. I had to call each county clerk and ask them if they had any judicial bypass requests from minors seeking abortions.

This informal calling of courthouses was how this part of the story was written:

Most officials of the state's smaller judicial districts had so few of the cases that they could say with certainty the exact number. Larger districts, such as El Paso County, used words like "a few" or "a handful" to describe their count of requests. Judge Karen Ashby, the presiding Denver juvenile court judge, said she has heard about 15 cases.

I don't remember if I never asked for the number of rejections from each judge, or if the judges mentioned above also said that they had never rejected a judical bypass request. Sloppy writing from me.

I get my most definitive number from Planned Parenthood:

No official numbers are kept by the state. But Planned Parenthood of the Rocky Mountains has connected 66 girls to a network of lawyers who volunteer their time to handle judicial-bypass cases, spokeswoman Kate Horle said. Not all of the girls have decided to go through with the process. For those who have, no judge has denied a bypass request, to Horle's knowledge. Kevin Paul, who as Planned Parenthood's legal counsel helped establish the network, said he is unaware of any denials.

My early assumption would be that the Colorado Republican state representative, Ted Harvey, would care enough to have kept a count, because he sponsored the parental-notification bill, ostensibly to protect minors and to reduce abortions. But, it wasn't a priority for him at the time (nor was it a decade later, from what I can tell).

Just goes to show, counting takes resources, and everyone who keeps count has an agenda. Planned Parenthood, which is the primary provider of abortion-related assistance. It would naturally have records for how many girls the organization helped, including how many needed help with parental notification and judicial bypass.

Furthermore, they had no problem sharing those numbers. Making known the number of abortions they help with is a measure of their impact. That judicial bypasses seem to be, by their counting, practically a rubber stamp, is something that aligns with their viewpoints on parental notification: that minors who need abortions generally have reasons that judges agree with anyway.

Igorning that this story is a bit too who-gives-shit?, given the paucity of data, it's at least a nice exercise in the power of counting, with just spreadsheet and phone.

Let's see how a professional handles this story.

Nationwide angle: Mother Jones's state-by-state view of parental notification

You can tell by the title and lede image and deck of Molly Redden's 2014 story that she and Mother Jones has some opinions on parental notification:

Headline: This Is How Judges Humiliate Pregnant Teens Who Want Abortions

Deck: Pregnant minors who fear their parents can turn to a judge if they want an abortion. But conservatives are turning the process into a nightmare.

But the non-objective voice in this story is backed up by solid, hand-collected data, namely:

Which states have mandated parental notification and/or tightened bypass rules

Mother Jones probably has a lot of agreement with Planned Parenthood. The map below can be thought of as a spreadsheet-to-map version of PP's state-by-state list of parental notification laws:

Further down in the piece is map-tabular hybrid that we saw in Mojo's statute-of-limitations-on-rape article:

This table shows the detail and scope of the research, and the specific angle of this piece. It's not just about parental notification, or about judicial bypass, but how judicial bypass more difficult for minors to bypass. And in Mojo's reporting, there are 5 ways for a state to make judicial bypass harder.

Like me, Mojo's reporter, Redden, doesn't have exact numbers on teen abortions performed for any state, though she is able to narrow down the annual number of bypass petitions in Florida to the "hundreds". Her reporting includes a review of 40 cases (I didn't get the paperwork for any specific cases), and she finds that, unlike Colorado, judicial bypass is not at all a rubber-stamp:

But a review of more than 40 cases, along with interviews with minors and their attorneys, reveals that in much of the country, obtaining a judge's approval to get an abortion is a mammoth struggle. "'Daunting' doesn't begin to cover it," says Jennifer Dalven, who runs the reproductive rights arm of the American Civil Liberties Union. "Imagine it: You're 17 years old. You're already struggling with this unplanned pregnancy. You may be afraid of your parents. And now you're told, 'Go to court'?"

Redden's take on parental notification laws may have too strong of an advocate point of view for mainstream journalism or an academic paper, but don't miss the solid research she did that was needed to create a compelling story.

Looking up laws nationwide is not beyond what you can do as an Internet-equipped Stanford student. Knowing the differences between states is not just trivia, but a powerful way to understand all the factors and forces behind a bigger debate. And for our purposes, this kind of research and info-collection is quite naturally, data collection and analysis.